It may sound funny, but the partnership that sent 33 Iowa kids to college started with an old, broken down Motorola radio. Well, that old radio and the incredible generosity of one hardworking Iowan.

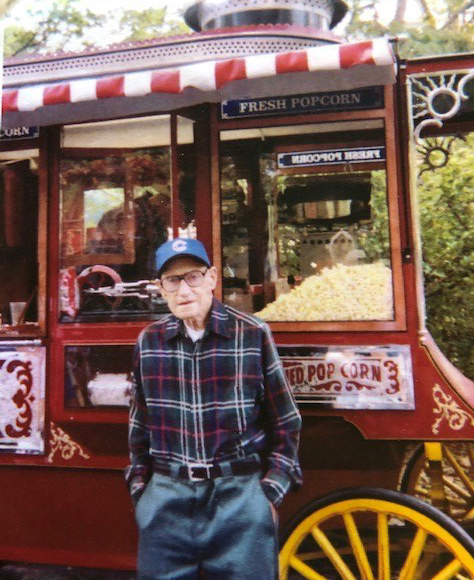

Modest, Hardworking and Humble

The aforementioned radio belonged to Walt Tomenga, who inherited it from his grandparents. Walt visited several radio shops to try and get it fixed but struggled to find anyone that could help him. He eventually got the name of Roy Nigg in Des Moines, who could help Walt get the radio working again. Walt looked up Roy in the phone book, gave him a call and went to see him.

The two struck up a friendship, and so did their wives, Judy Tomenga and Lila Nigg. But something peculiar would happen when the couples had get-togethers at Roy and Lila’s house. As Walt and Judy arrived through the front door, there was always the echo of the back-screen door on the house slamming shut as someone else departed. The source of the noisy exit turned out to be Dale Schroeder, Lila’s shy younger brother.

One day, Walt decided to surprise Dale before he could sneak out and avoid conversation. As always, Dale snuck out the back, but this time walked right into Walt’s outstretched hand. Walt introduced himself, and although Dale didn’t open up right away, the two would become friends over the years.

Dale worked as a carpenter at Moehl Millwork in Des Moines, a humble job, but one he took pride in. He came from a modest background. Raised with his sister, Lila, by their single mother, Dale didn’t even have his own bedroom until he was well into adulthood. With no spouse or children, he threw himself into his craft with a strong work ethic and commitment to doing a good job.

Walt and Judy would occasionally have family and friends over to their house for dinner, and as Walt and Dale’s friendship grew, Dale was also invited. The first few times, he ate his food and left, saying as little as possible. Always shy, Dale took a while before opening up, but as a preview to his plans for later in life, he enjoyed connecting with the younger folks at dinner and would engage in conversations with them lasting sometimes 30-45 minutes at a time.

Dale’s Secret

Over the years, Dale accumulated quite a few Social Security checks he never cashed. Walt claims the stack was nearly an inch and a half thick. With all those checks sitting around, Dale asked Walt, who had been involved with many charities throughout his life, for his opinion on which charities his hard-earned money should go to.

“I gave him my opinion of which [charities] are the most effective. He listened very intently, and then told me ‘No, I don’t want to do that,’ after I explained it for about 20 minutes,” Walt said with a laugh.

What Dale really wanted to do with the money was provide kids with an opportunity he never had — to go to college. He particularly wanted to help kids from small towns in Iowa who had had challenging upbringings or limited resources. Dale also sought input from his lawyer, Steve Nielsen, about what to do with the money. What Walt and Steve thought to be several hundred thousand dollars turned out to be a much larger sum — just shy of $3 million.

“I had no idea he had seven figures,” Steve said. “I about fell out of my chair.”

The Dale Factor

Sending kids to college was an easy idea to think of — pulling it off was not. It would have been much easier to give the money directly to one school, but Dale wanted Steve and Walt to manage it, distributing it to people rather than institutions.

After Dale passed away in 2005, the group, led by Walt, Judy and Steve, kept Dale’s vision moving forward. They partnered with Acing the Test (ACT) to get the word out to schools in small towns, ensuring they would reach the right type of students. ACT would whittle down anywhere from 600-800 applications per year for a final consideration set of 20.

“We were looking for people like Dale. In spite of a stacked deck, they were still fighting,” Steve said.

Applicants wrote four essays based on prompts and were graded on a weighted point system. The group graded the essays independently and interviewed eight of the top 20.

Those eight finalists met at a church in central Iowa for interviews so the team could assess which kids had the “Dale Factor.” None of the eight went home empty-handed. Four of the finalists received a one-time $5,000 scholarship, while the other four received a full-ride scholarship to Iowa State University, the University of Iowa or the University of Northern Iowa. The group paid for four total years of school, so those applicants who had earned college credit in high school could take advantage and apply some of the funding toward grad school.

The group had to apply for nonprofit status as a 501(c)(3) organization, which took more than a year. They brought an accountant on board to ensure financial integrity and continued to work through the business of managing a scholarship program. The group was even audited three times during this process.

“No one believed we were all doing this for free,” said Steve.

For the kids that received the scholarships, Walt and Judy became an invaluable resource. Judy was thought of as a second mother to many of the students who went through the program.

“Part of it has to do with my experience educating, I’ve had a variety of experiences that brought me to that time and understanding where a young person comes from,” Judy said.

With Walt’s background as a counselor and Judy’s experience as an educator, the two made a great pair in ensuring open lines of communications were kept with the students. Specific criteria had to be met to maintain funding — things like GPA, good behavior and employment.

“It was about finding ways to help them be successful when hurdles came. If they tripped over the hurdle, it was about getting back up and over the hurdle.”

Dale’s Kids

The scholarships started in 2007, with the last class of recipients entering college in 2015. Over that time, 33 Iowa students received a free college education because of the selflessness of one hard-working Iowan with some help from his friends.

Every year, Walt, Judy, Steve and the recipients met for a reunion dinner at Trostel’s Greenbriar Restaurant in Johnston to honor the legacy of Dale.

“They all asked about him,” said Steve. “We kept him alive by telling his story. That’s the fun part. And they’re all just floored by his story and generosity.”

Though they were never able to meet him, Dale left an indelible impact on each and every one of those students. The group has nicknamed themselves “Dale’s Kids,” and are now doctors, teachers, therapists and more, impacting Iowa and the world in ways that would have made Dale proud.